The Scrap That Built America : A Short History Of Metal Recycling In The United States

- A&A Recycling

- Jan 13

- 7 min read

I've been doing this scrap metal recycling thing for a long time. I've also had the privilege of working with people who have been at it much longer than I have. One of my favorite things in conversations with them was to get them reminiscing about the good old days of scrap metal. I loved hearing stories of how the industry was back then, and comparing it to how we do things today.

One memory in particular still stands out to me today. I was just a young buck, new to the industry, I was talking to a gentleman who had been in the industry for quite some time. His family had also been in the trading industry for a long time. He pulls out a leather bound ledger book and opens it to a particular page, he then showed me a line on the ledger page detailing that they used to also trade fur pelts, as well as paper, and metals. I was always struck by that conversation, why were they trading furs when they were in the recycling industry? One day it hit me. The "Recycling" industry that we know today has evolved from the "Trading" industry. So I decided to take the liberty and do a deep dive into how we got to the recycling industry that we all know today.

Let's Start With 1776 Shall We?

During the Revolutionary War, scrap metal wasn't yet exactly an "industry", reusing things was a matter of survival. We didn't yet have steel mills that we see today or factories to support the Revolutionary Army, so back then, they had to be resourceful. The practice of "salvaging" was more on point than "recycling". It was expensive at the time to import lead, steel, or brass, so after battles it was was common practice to do "salvage walks" on the battlefield to collect items from fallen soldiers. Among the items collected would be weapons, musket balls, cannon fragments, and iron fittings. These items would be returned into the supply chain to be made into more supplies. There are also instances where brass church bells or public bells were melted down and cast in order to make cannons.

During the Revolutionary War, salvaging materials was the difference in winning our independence or losing to the British. A stark contrast from what the booming industry that we know today.

The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution is where scrap metal stopped being a habit and became infrastructure.

As factories, railroads, and mills expanded in the mid-1800s, they produced metal waste at a scale never seen before—worn rails, broken machinery, defective castings, and cutoffs from mass production. This wasn’t trash. It was raw material waiting to be remelted.

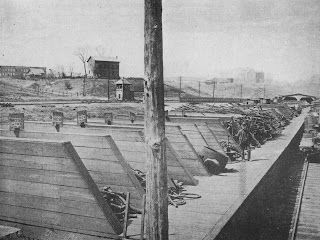

Railroads became the largest sources of scrap in America. Iron rails wore out quickly, spikes and couplings failed, and entire lines were upgraded or abandoned. Old rail iron was pulled up, sold, and melted down into new steel, often transported on the same rail lines that created it. Scrap followed industry, and railroads made it movable.

This era also gave rise to the independent scrap dealer. Individuals collected metal from factories, rail yards, farms, and demolition sites, aggregating material and selling it back to foundries and mills. Pricing emerged based on type, weight, and quality—laying the groundwork for the modern scrap market.

Steelmakers quickly learned that scrap was an advantage. It melted faster than raw ore, required less fuel, and lowered production costs. By the late 1800s, scrap was intentionally blended into steelmaking. Waste had officially become feedstock.

Urban growth accelerated the process. Cities were constantly tearing down and rebuilding, and iron beams, pipes, and structural steel were salvaged rather than discarded. Buildings were dismantled, not demolished—cities became above-ground mines.

By the end of the Industrial Revolution, scrap metal was no longer accidental. It was strategic. Mills depended on it. Dealers supplied it. Prices moved with demand. The scrap yard wasn’t a byproduct of industry—it was one of the systems that made industrial America possible.

Scrap Metal Goes To War: WWI & WWII

World War I and World War II marked a turning point for scrap metal recycling in the United States. During both conflicts, industrial output increased rapidly, and access to raw materials became a critical concern. Scrap metal provided a reliable and efficient source of material to support wartime production.

World War I

During World War I, the U.S. government encouraged the recovery and reuse of scrap metal to meet the growing demand for steel, copper, and brass used in ships, weapons, vehicles, and infrastructure. Manufacturers redirected factory scrap back into production, and scrap dealers played a growing role in supplying mills. While scrap drives were smaller and less centralized than in later years, the war established scrap metal as an important component of national industrial capacity.

World War II

World War II expanded scrap metal recycling to an unprecedented scale. Federal agencies organized nationwide scrap drives and promoted public participation through posters, advertisements, and community programs. Citizens were encouraged to donate unused metal items such as cars, appliances, farm equipment, household goods, and tools.

Local governments and private scrap dealers coordinated collection and transportation, moving large volumes of material to steel mills and smelters. Recycled steel, aluminum, and copper were used extensively in military production, including vehicles, aircraft, ships, and munitions.

For the first time, scrap metal recycling became widely recognized by the public as a necessary part of the war effort.

Lasting Impact

After World War II, the systems developed for wartime scrap collection and processing remained in place. Scrap metal continued to be a primary feedstock for steel production, and the scrap industry became more organized, regulated, and technologically advanced.

These wars demonstrated that recycled metal was not only economical but essential to large-scale industrial production. The role of scrap metal recycling was firmly established as part of the U.S. manufacturing and supply chain—a role it continues to play today

The Post War Era

After World War II, the United States entered a period of rapid industrial growth. Manufacturing expanded, infrastructure projects accelerated, and consumer goods—especially automobiles and appliances—flooded the market. This surge created an entirely new challenge: how to process scrap metal at volumes far greater than anything seen before.

To meet demand, scrap recycling shifted from largely manual operations to mechanized, high-throughput systems.

One of the most significant developments of the post-war era was the introduction of the automobile shredder in the late 1950s and 1960s. As millions of vehicles reached the end of their service life, dismantling them by hand was no longer practical. Shredders allowed entire cars to be processed quickly, reducing them into small, furnace-ready pieces and dramatically increasing the amount of ferrous scrap that could be recovered. This technology transformed vehicle recycling and remains a cornerstone of modern scrap processing.

Hydraulic shears also became standard equipment during this period. These machines allowed scrap yards to cut heavy steel—such as beams, plate, rail, and industrial equipment—into manageable sizes efficiently and safely. What once required extensive manual labor could now be accomplished in minutes, improving both productivity and consistency.

Scrap balers gained widespread use as well, particularly for light steel and nonferrous metals. Balers compressed loose material into dense, uniform bundles, making storage and transportation more efficient and reducing handling costs. This improvement helped scrap move more easily through regional and national supply chains.

Material handling equipment advanced rapidly during the post-war years. Cranes with magnetic attachments replaced much of the manual loading of heavy ferrous scrap, while forklifts became common throughout scrap yards. These machines allowed yards to process more material with fewer labor hours per ton and improved overall safety.

By the end of the post-war era, scrap metal recycling had evolved into a fully industrial operation. Yards were larger, equipment-driven, and closely integrated with steel mills and manufacturers. Scrap was no longer just salvaged—it was processed, standardized, and engineered for reuse.

This period laid the groundwork for the modern scrap industry, proving that recycled metal could be handled at massive scale and serve as a reliable, primary input for American manufacturing.

The Scrap Industry Today

Modern scrap metal recycling is the result of decades of industrial refinement. What began as manual salvage and post-war mechanization has evolved into a highly engineered, data-driven industry that plays a central role in manufacturing, infrastructure, and global trade.

Today’s scrap yards operate as material recovery and processing facilities. Advanced automobile shredders can process hundreds of tons per hour, breaking down vehicles and heavy scrap into consistent, furnace-ready material. These systems are paired with powerful magnetic separation to efficiently recover ferrous metals, ensuring clean feedstock for steel production.

Nonferrous recovery has seen some of the most significant technological advances. Eddy current separators allow aluminum and other nonferrous metals to be separated from shredded material at high speed. Optical sorting, sensor-based detection, and air classification systems further refine material streams, improving recovery rates and reducing contamination. These technologies make it possible to extract value from material that would have been unrecoverable in earlier eras.

Modern material handling equipment has also transformed yard operations. High-capacity cranes, grapples, forklifts, and automated conveyors move scrap efficiently and safely through processing stages. Integrated scale systems and digital tracking ensure accurate weights, transparent pricing, and detailed inventory control—something unimaginable in early scrap operations.

Environmental controls are now a standard part of scrap recycling. Dust collection, stormwater management, noise mitigation, and regulated material handling practices allow modern facilities to operate responsibly within urban and industrial environments. Recycling metal today requires not only efficiency, but compliance with environmental and safety standards.

Perhaps most importantly, modern scrap metal recycling is deeply connected to the global economy. Scrap prices and demand are influenced by domestic manufacturing needs and international markets. Recycled metal is routinely shipped across regions and borders, supplying mills, foundries, and manufacturers worldwide.

In the modern era, scrap metal recycling is no longer defined by what is thrown away. It is defined by what can be recovered, processed, and returned to use. The scrap yard has become a critical link in the circular economy—turning end-of-life materials into the raw inputs that build the next generation of infrastructure, products, and industry.

Thanks for taking this journey through time with me. Until next time, stay scrappy.

.png)

Comments